P. T. BARNUM

The name Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810-1891) is synonymous with the circus.

He is, after all, the Barnum of Barnum & Bailey which, upon merging with Ringling Bros. following the deaths of both Barnum & Bailey, became America’s longest running circus, pitching up for the final time in 2017.

On the contemporary popularity of Mr P. T. Barnum, historian James W. Cook asserts:

“Barnum was the most widely visible and widely known American of the nineteenth century. It’s not an American president, it’s not a scientist, or someone who actually achieved […] a breakthrough to improve humankind. It was a showman.”

Cook also credits Barnum as being an, if not the, central figure in the institutionalisation and commercialisation of ‘freakery’ as “a dominant theme in nineteenth century mass entertainment…”

JOICE HETH

In 1853, Barnum made a purchase that epitomises his morally-questionable career in the circus. His acquisition was a slight and elderly African-American slave, named Joice Heth.

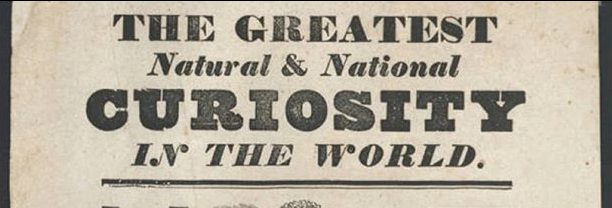

Soon, the streets of New York were plastered with posters boasting the exhibition of former-president George Washington’s very own nursemaid. Her age was stated as 161 years.

As was all too common in this era, Heth lead an existence devoid of free will. Her performance under Barnum’s instruction was no different. Despite this, however, she played her role convincingly and the scam was a success. Thousands visited her, paying Barnum 25¢ a head, and reports in the press did not suggest any suspicion as to the honesty of the claim.

The pair toured the states, pulling crowds and collecting pennies, but by the time they had reached New England, interest was dwindling. A businessman above all else, Barnum made the radical decision to publicly – and anonymously – accuse himself of fraud via notifications in newspapers.

These new, masked advertisements claimed Heth to be an automaton composed of Indian rubber and mechanical springs… In other words, a robot! The genius of this publicity stunt was that Barnum now had cause – albeit fabricated – to invite the public to visit the attraction and decide for themselves.

Though Barnum cannot be credited with the creation of the circus (that can be read about here), with his touring of Heth, he placed the travelling Freakshow at the centre of the history of the tradition… and along with it decades of hugely problematic human exploitation.

In respectful memory of these derogatively dubbed ‘Freaks’, Generally Gothic invites you to peek behind the curtain and take a look at the humans beyond the well-known stage personas.

The following four circus performers were voted for by you on Instagram. Follow along there to help shape future content and get involved!

ANNIE JONES

Becoming America’s most famous ‘Bearded Lady’ during her adulthood, Annie Jones (1865 – 1902) was thrust into the circus life before she was even a year old. An almost life-long member of P. T. Barnum’s travelling circus, Jones performed as one of the showman’s most famous ‘Freaks’.

Aware that she was being unfairly represented, Jones took issue with the title ‘Freak’ and, as acting spokesperson for her likewise-labelled peers, advocated for the abolition of the word. Popular in royal courts, taverns, and fairgrounds, ‘Freak Shows’ have existed since the sixteenth century; whilst Barnum was innocent of coining the derogatory term, Jones’ efforts did little to discourage his use of it.

Perhaps caused by hirsutism, Jones’ facial hair was well-kempt and of no deterrent effect to suitors. She married Richard Elliot, a sideshow barker (who turned passersby into the circus audience) aged just fifteen, eventually divorcing him a decade and a half later for William Donovan, her childhood sweetheart by some accounts.

The pair of lovers performed as a touring duo for just four years, abruptly stopping with the unexpected death of Donovan. With nowhere else to turn, Jones returned to life as the ‘Bearded Lady’ under Barnum’s big top, eventually dying of tuberculosis before the age of forty.

Remembered today not only as one of the most successful bearded ladies of all time, but also generally as one of Barnum’s most memorable performers, it is hard not to wonder what Jones would have thought about still being referred to as a ‘Freak’ over a century after her death…

DAISY AND VIOLET HILTON

Born fused together at the pelvis in Brighton, England, in 1908, Daisy and Violet Hilton were the first documented conjoined twins to survive beyond a few weeks in the UK.

Raised by their single mother’s abusive employer, Mary Hilton, they began touring and performing aged just three. On Mary’s death, the sisters were passed into the care of the former’s own daughter, who continued her family’s tradition of exploitation and abuse, now in the USA.

In 1931 Daisy and Violet finally gained their freedom, entertaining first in vaudeville and then burlesque circuits, eventually becoming two-time stars of the silver screen (Freaks, 1931, and Chained for Life, 1952).

Over the decades, interest dried up until eventually their tour manager abandoned them, penniless, following their final performance at a North Carolina drive-in cinema in 1961. With no choice but to remain in North Carolina, the Hilton sisters lived out their days as assistants to a greengrocer.

Eight years after their last public appearance, the twins were found dead in their home having failed to show up for work. Daisy is believed to have succumbed to the Hong Kong flu first, following by Violet up to four, excruciating days later.

Having suffered a hard life of exclusion, constant work, and poverty, the Hilton sisters ended life as they began it – not as circus ‘Freaks’ but as regular people. Although theirs is a sad story, there is comfort in knowing that they almost always had each other.

ISAAC W. SPRAGUE

Also known professionally as ‘The Thin Man’ and ‘The Living Skeleton’, The Skeleton Man’ Isaac W. Sprague was born without fanfare in Massachusetts, USA, in 1841.

The onset of his illness was marked with a complaint of cramp following a swim, aged twelve. Despite maintaining an enormous appetite, Sprague continued to inexplicably lose weight from this moment onwards.

In his early twenties, with both parents dead and illness making a return to past employment impossible to endure, Sprague joined the circus in 1865 and Barnum’s American Museum the following year.

Before the marketing tradition of ‘Thin Man and Fat Lady’ shows, wherein the paired performers were always wed, the original ‘Thin Man’ left Barnum to marry Tamar Moore and father three healthy sons.

Born a free male, Sprague was never forced into the circus, but his disability left little other choice. Now with a family of his own to support, a gambling habit and his declining health, the reluctant performer returned to the circus out of necessity.

Unable to find his riches there, by 1882 he had received a diagnosis [“extreme, progressive muscular dystrophy”], donated his body to Harvard Medical School for $1000, divorced his wife, and begun a double act with his new wife – an unsuccessful beauty pageant contestant, named Minnie Thompson.

A gambling man to the end, some sources claim that Sprague wagered during his final show on a Monday that he would not survive until the following Saturday.

In this story, luck was unkind to him, even in death; he is fabled to have lost the $250 bet and died weighing just 43lbs/19.5kg/3.08stone the following Tuesday. The New York Times, however, reported on Friday the 6th of January, 1887, that Sprague died the day before – on a Thursday.

Though the specifics of his death are shrouded in lore, it is important to remember him as a man, for his faults and successes, and hard efforts to simply survive in a world where no one but the exploitative Barnum would employ him.

SARA BAARTMAN

Sara Baartman is known by many names, but most memorably ‘Hottentot Venus’. This stage name is in reference to her indigenous South African Khoikhoi ethnicity – previously and perjoratively referred to as ‘Hottentots’ – combined with the Roman Goddess of love.

She was born sometime in the latter half of the eighteenth century in the then-Dutch colony, The Cape of Good Hope, in South Africa. In 1810 she was taken to England by Hendrik Cesars, a free man of slave descent, and William Dunlop, an English doctor. She was relocated with the men’s express intent of displaying her for financial gain.

Her stage performances in Piccadilly, London, angered British Abolitionists who feared for her well-being. Whatever the truth, Dunlop prevailed in court and went on to show Baartman in county fairs without Cesars.

Four years later, following Dunlop’s death, Baartman sadly did not gain her freedom. Instead, she was bought by a man named Henry Taylor who took her to Paris, and in turn sold her to animal trainer, S. Reaux. As ‘an experiment’ the continually mistreated Baartman was forced to bear a daughter by Reaux, who died at five years of age.

The last of a long list of men to get his hands on her, was George Curvier. As founder of the Museum of Natural History, he studied Baartman seeking to prove the existence of a genetic missing link between humans and animals.

The long-suffering Baartman died in poverty in 1815 in Paris, whereupon Curvier took claim of her body, placing her brain, bones, and genitalia on display at the Paris Museum of Man. Her remains were kept there until 2002, when she was finally returned to South Africa for burial on the country’s National Women’s Day.

Scholars have pinpointed her mistreatment as the beginning of decades of the black, female body being misrepresented by the west. Over recent decades, Baartman has become a continued subject of feminist study and art, which aims to pay her the respect that she rarely experienced in life.

By framing the many men and women who performed in his Freakshows as ‘other’ than human, Barnum reveals the dark and gothic underbelly of his circus – one which grew fat on exploitation, and the encouragement of fear and separation based on physical dissimilarities.

Othering is a common trope in early gothic fiction, predating and coexisting with Barnum’s circus. In some literary cases, it was employed as social commentary. In others, a simple scare tactic. The unavoidable reality, however, is that ignorance has, in our collective past, led to an enduring misunderstanding of one another based upon a whole host of insignificant factors. Rather than celebrate the Freakshow as spooky history, the aim of this article is to highlight that – as early gothic fiction has taught us – it is easy to misidentify monsters, and men. All we need do is pay a little attention and the distinction, though perhaps unexpected, will become clear.

‘A Brief and Gothic History of the Great, American Freakshow’ is published as part of the Circus of Horrors series on Generally Gothic. Read more with ‘Found Circus Photographs: Forgotten in the Mitten Interview’, ‘Sawdust & Sequins: The Art of the Circus’, and ‘Beneath the Big Top: Interview with a Circus Artist’.